Why the world relies on a Chinese “perspective”

Virtually every architect, engineer and designer in the world today relies on axonometry, a projection system first used in China about 2000 years ago. Axonometry is the Chinese alternative to European linear perspective and was used by both Chinese artists and architects. Yet few books on art history mention the origin of axonometry and what it can tell us about the Chinese worldview.

The projection of three-dimensional space on the two-dimensional picture planes was an elusive goal throughout the world. All early art was two-dimensional. Artists lacked a graphic tool to depict 3D space on the 2D picture plane.

About 2500 years ago, Greek artists “open the door” to linear perspective when they depicted man-made objects that seemed to recede from the picture plane. The overall pictorial space was not yet coherent, but the open door suggested depth on the 2D surface.

More than a thousand years later, Italian Renaissance artists took the next step when they invented the so-called vanishing point. The lines of projection converge at an imaginary point at the horizon. The vanishing point enabled artists to depict a coherent pictorial space on the 2D picture plane. Linear or scientific perspective, together with claire-obscure, formed the basis of Europe’s pictorial language until the 19th century.

A Chinese perspective

About 2000 years ago, the Chinese developed dengjiao toushi, a graphic tool probably invented by Chinese architects. It came to be known in the West as axonometry.

Unlike linear perspective, axonometry is not based on optics. It has no vanishing point. Pillars and beams remain strictly parallel, unaffected by optical distortion. The size and geometry of all man-made objects remain constant, regardless of the position of the viewer.

Space and time

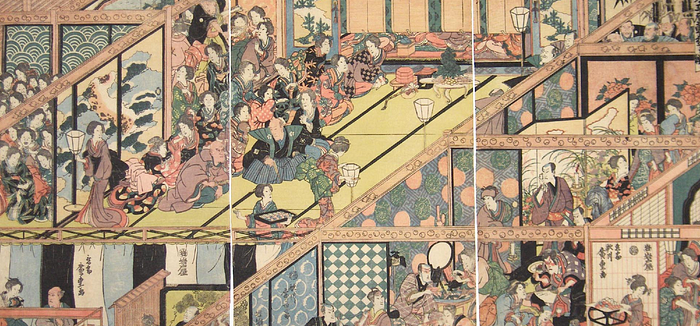

Axonometry was crucial in the development of the Chinese hand scroll painting, an art form that art historian George Rowley referred to as “the supreme creation of Chinese genius.” Classic hand scroll paintings were up to ten meters in length. They are viewed by unrolling them from right to left in equal segments of about 50 cm. The painting takes the viewer through a visual story in space and time.

A scroll may depict life along a river. We unroll the opening sequence of the scroll and see people boarding a boat on a river. As we unroll the scroll further from right to left, we see the boat cross a lake, navigate rapids in the river, stop at a small harbor, and lastly arrive at its destination at the seashore. We have traveled through the landscape (space) in the course of the day (time).

Importantly, the scroll is not a sequence of separate scenes. It is a continuous, seamless image. This explains the importance of axonometry. When a building comes into view, it is depicted in axonometric projection. Linear perspective, which assumes a fixed position of the viewer, could not be used in the pictorial scroll format. With axonometry, which lacks a vanishing point, the focus is everywhere and nowhere.

Video of Chinese had scroll as synthesis if space and time

Introduction to Europe

Jesuit missionaries based in China brought illustrations of axonometry back to Europe in the 17th century. The exotic graphic device was initially used for diamond cutting, ballistic measurements and other technical measurements. Its wider acceptance came in the 19th century, when English scientist William Farish, using Euclidean geometry, developed isometry. It gave axonometry a mathematical foundation.

Farish published a paper entitled ‘On Isometrical Perspective’ in which he made clear the Industrial Revolution needed technical working drawings free of optical distortion.

Modernist embrace

The popular acceptance of axonometry came in the 1920s, when modernist artists and architects discovered its value in depicting modern, industrial architecture. De Stijl architects Theo van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren caused a sensation in Paris when they presented axonometric renderings of their designs. Today, axonometry is used by architects, engineers and designers all over the world.

Axonometry was also crucial in the development of Computer Aided Design and subsequent forms of visual computing. Our modern world is virtually constructed in axonometry. However, its Chinese origin and the worldview that created axonometry has been largely ignored.

Axonometry is the reflection of the ancient Chinese thought that space and time are intrinsically related — in modern terminology a space-time continuum. The Chinese notion of space-time was probably formulated by Chinese ancient Feng-Shui masters. Historian Feng Yu-Ian explained that the Chinese in ancient times Chinese spoke of Yu, which means ‘space-universe’. They also spoke of Zhou, which means ‘time-universe’. A little more than 2000 years ago, these words began to appear together: Yu-Zhou.

Yu-Zhou represents the yin-yang universe. Yu is yin, Zhou is yang. Feng Yu-Ian noted that the scholar Lu Xiang-shan was reading an ancient book and came upon the characters Yu and Zhou. The explanation said, ‘What comprises the four points of the compass together with what is above and below: this is called Yu. What comprises past, present and future: this is called Zhou.’

Yu-Zhou and axonometry appeared to have been conceived at roughly the same time. One can be used to illustrate the other.

Axonometry and its geometric cousin isometry were an invaluable addition to linear perspective. American author and architect Claude Bragdon, author of The Frozen Fountain, offered what must be the best description of its aesthetic qualities. He wrote:

‘Isometric perspective, less faithful to appearance, is more faithful to fact; it shows things nearly as they are known to the mind. Parallel lines are really parallel; there is no far and no near, the size of everything remains constant because all things are represented as being the same distance away and the eye of the spectator everywhere at once. When we imagine a thing, or strive to visualize it in the mind or memory, we do it in this way, without the distortion of ordinary perspective. Isometric perspective is therefore more intellectual, more archetypal, it more truly renders the mental image — the thing seen by the mind’s eye.’